On a windy February lunchtime, I set out for the Natuurtuin (natural garden) in Wageningen University grounds.

The board explained that the garden was laid out using local soil types. Along the edge of the path leading to the large pond, heaps of earth have been brought to the surface.

Green shoots were springing through the mole-hills.

A gentle sound of bricks being tapped into place came from the adjacent block of ground, with a swish of sand being swept across them.

A pump suggested underground construction. I had learnt from the notice-board that rainwater from the large pond is used as grey water in Lumen (one of the university buildings).

Further along the path, I saw that the natural garden is bounded by a heap of rubble. I am learning to see this as a sculpture – a work in more-than-human progress.

I was prompted to read more about this artwork which was created in 1996 by the sculptor Krijn Giezen. He was known for re-using debris to create structures that might eventually be seen as a natural part of the landscape, as plants grow over them. Giezen proposed a hollow wall that would with time provide shelter for wildlife, including bats.

This proposal for a Shelter and Overwintering Place for Flora and Fauna seems to have been criticised by staff. Some people were uneasy about the use of waste materials, and could not envisage what the completed work would look like. The installation was also complicated by the municipality’s requirement for both a building and environmental permit.

Despite being reduced in scale and scope, Giezen’s work survives as a refuge amidst new building work.

Trees are slowly becoming established. This work really grows on me too.

I returned on an even wetter day to see what creatures might be using the shelter, and realised that this artwork must be watched over time. Perhaps video conveys the place better than a photo can; you can see and hear the raindrops on this short clip:

Parts of Giezen’s wall seem to have become a research site. I assume the way some trees are wired up means that they are being studied.

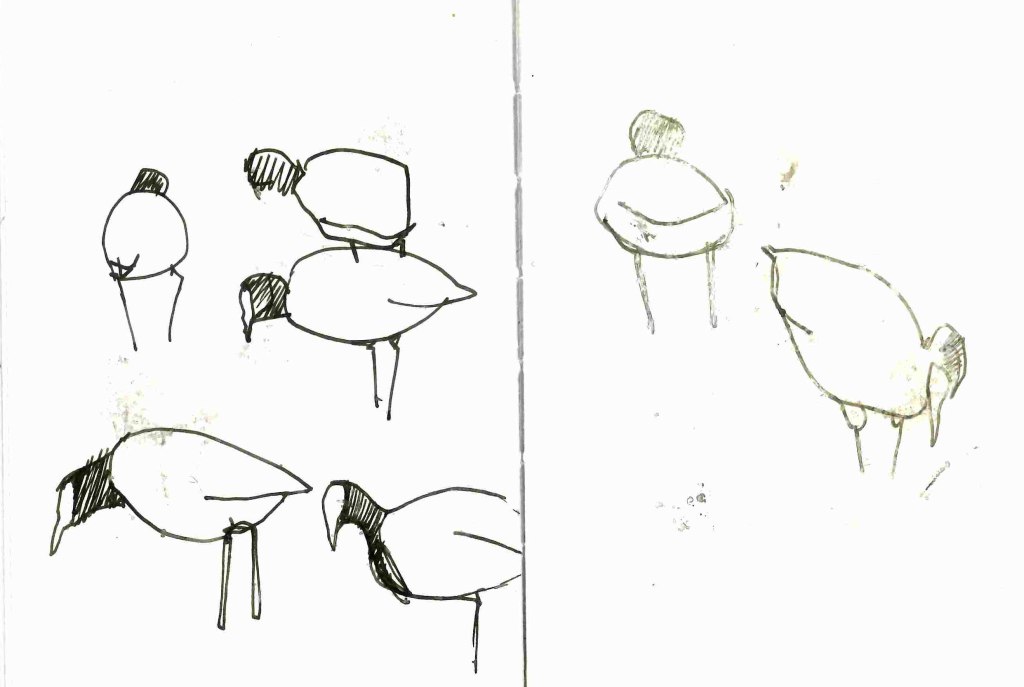

A Coot was foraging by the banks of the large pond, unperturbed by the water-drops running off its back.

The natural garden affords different kinds of foraging and shelter; it is a place with heaps of possibilities within a University of Life Sciences. I appreciate the pioneering environmental art of Krijn Giezen: right behind the bike-sheds, he has created a place that rewards attention.

Postscript

The next day, the builders took the barrier tape away. Pieter Slim kindly guided me to the focal point of the wall which I had not been able to see earlier. At the western edge, there is a tailor made entrance for hibernating bats – protected from martens who are also catered for.

This post is one in a series of #wetlandsketches in and around Wageningen University, a centre of expertise in the Life Sciences. As author of this post, responsibility for the content, and any unintended errors, is all mine. My thanks to Pieter Slim for highlighting Giezen's project. Reference: Jansen, B, Ruyten L, de Windt, R and Zaal, A. (Editors) Lumen, Gaia, Atlas: Architectuur, kunst en tuinen van de gebouwen van de Environmental Sciences Group. Wageningen University: 2010.